BEV vs. PHEV: A Sensible Compromise

The electrification of the automobile is well underway and it is realistic to think that every new vehicle will have a 240V plug and a battery pack in the next 10 to 15 years: either a Plug In Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) or Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV). It is reasonable to expect that, at least in western countries, government and industry might agree to regulations that specify that every new light duty automobile sold must have the capability to drive with zero tailpipe emissions for a certain distance and in certain places. Mandating fully electric EVs, giving up ICE and liquid fuel, may be much more difficult - at least in Canada.

Questions are:

Will we be able to make the change to entirely BEV in this time frame, and if not, what will be the split between BEV and PHEV?

Will the manufacturers who have pledged to eliminate ICE vehicles (which would include PHEVs) walk back their mandates, or give up market share and limit distribution of EVs to those areas where their is a demand?

What is the organic rate of consumer adoption of EVs and how does this differ dependent on location?

What affect do Government incentives have on the adoption rate of EVs, and how does this differ by region?

What social factors limit the adoption of electric vehicles?

Let’s start with the consumer. At least en masse, the consumer is going to purchase an EV if it offers more utility at lower cost than an ICE. The utility of the EV is in large part the net of the EV benefits - performance, refinement, not stopping for gas, climate pre-conditioning - weighed against difficulties charging and range. The cost of an EV is currently greater than an ICE vehicle, but the cost of operation is lower. When the utility/cost relationship is favourable then there will be EV adoption - at least if there is supply.

Government policy has a huge effect on both the economics of owning and EV and the charging infrastructure which dictates the utility for many people. Population density is a main factor in determining the economics of building out a fast charge network.

Globally, we see huge variations with EV adoption. In Norway just about every passenger car sold is electrified, with BEVs accounting for about 70% of new car sales. In Saskatchewan the number is under 1% BEVs. Alberta might be 2%. BC is a North American leader with about 20% BEVs, matching Europe and China. The US has about 6% adoption and Canada averages about 5%. Globally we are at about 13%. The differences are due to many factors: Government subsidies, rebates, taxes, electricity cost, charging infrastructure, preferential parking and express lanes etc.

For reasonably convenient travel on the highway you need ‘Level 3’ DC charging stations with a minimum rating of 150kW, placed every 100km. With a 150kW rating, your EV may average anywhere between 50kW and 75kW if charged from 20% to 80%. Most EVs use between 20kWh and 25kWh of electricity per 100km at highway speeds. This means that the ratio between driving and charging will be between 2:1 and 3:1 depending on temperature. EVs with more advanced power electronics can get this ratio up to 4:1 or greater if they are matched to a 350kW station.

The stations need to have an adequate number of charging bays and they should have washrooms, garbages and wifi. If you divide the 3,500 Electrify America charging stations into their $2B investment you get to about $500k per charging station. This ‘back of the napkin’ math may be simplistic, but it gives an idea what the investment would have to be to give the prarie provinces adequate coverage to make highway driving reasonably convenient for EV owners. Private enterprise will not cover these costs; the Billions of dollars of investment would need to come from Government.

This then brings us to the social issues. The people that elect the government in the prarie provinces - that make most of their money from oil - may not want their elected officials spending Billions of tax payer dollars on an EV infrastructure that they don’t want, to drive an EV that gives them less utility than the ICE vehicle they are perfectly happy with. Where is a solution there?

Many people on the far right of the political spectrum view electric vehicles as nothing short of a Communist plot, and wouldn’t buy one at any price. To a fairly significant slice of the population, having the government tell them what kind of car they should buy is a non-starter, as is inefficient use of public funds. Many of my clients have broad automotive interests, but will tell me that there is no way they are buying one of those 'lady shavers', as Jeremy Clarkson calls them.

This is why I don’t see liquid fuel going away anytime soon in Canada. BEVs offer better utility at the same or lower overall cost than an ICE equivalent - providing you drive in or around the city and you have a place to charge it. This may reflect the reality of half of Canadian households. Subtract those who can’t afford a new car or those with political objections to the idea, and the buying pool decreases. I see these issues creating a natural limit to EV adoption. I think we will see continued strong growth of EV sales - it would help if they could make the cars - until we approach 30%-40% nationally. Vancouver may very well get to 75%, but Saskatchewan may never get above 20%. I really don’t see how it is going to get any higher than that in the forseeable future.

Manufacturers that have mandated 100% BEVs by certain dates will have to decide how important parts of the Canadian market are to them. No doubt there will be some car companies that will be happy to sell consumers the vehicles that they want to buy. They will also need to think about their dealers, and the benefit they have from a national service network. When it comes to losing market share and shuttering dealers, I think that those manufacturers will make the decision to keep PHEVs in production.

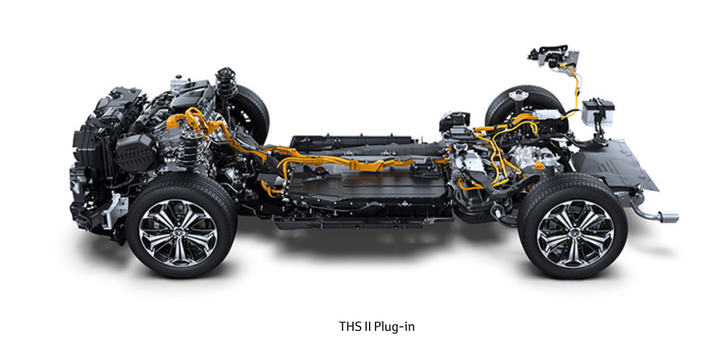

A sensible compromise would be to legislate that every new car has at least 50km of zero emission range and phase out combustion engines in the cities. For rural owners the PHEV with a 20kWh battery pack could be put to use as a mobile or emergency power source which would offer some extra utility even if they never use the electric motor on the highway. In this scenario overall liquid fuel use would drop to a small fraction of what it is today, but it would still allow convenient long distance travel over less populated areas. The investment on EV charge infrastructure could then be concentrated on major highways, which would make sense for private enterprise.

Comments ()